February 2021 saw most schools in Nepal reopen and function as ‘normal’ after putting health and safety precautions in place. Several schools divided their students into groups of two or three to ensure that social distancing protocols could be implemented efficiently, with each group attending in-person classes 2-3 times a week. Santwana Mishra, a teacher at a private school in Nepal noted that “there was finally some hope in the atmosphere” and that she had never seen students so excited to be back at school. “It finally felt like we were nearing the end of a painful catastrophe that robbed children of an entire year of their school experience.”

Unfortunately, this hope was short lived. On Sunday, 02 May 2021, Nepal recorded its highest peak in cases with as many as 7,137 people testing positive. In mid-March, the figures of COVID positive cases had dropped to double-digits. In just the past week, the number of people testing positive for COVID have increased by 136.8% . The sudden rise in cases is attributed to the presence of the double mutant/Indian Variant of the virus as well as the UK variant in the country, both of which are said to be more contagious in nature. Hence, only after a month of acknowledging the first COVID-19 lockdown anniversary, the Nepalese government had to yet again issue a directive on 26 April 2021 advising all schools and educational institutions to remain closed until further notice . After imposing strict lockdowns in several regions across Nepal, the government also decided to postpone all physical examinations until further notice.

The Official Portal of the Government of Nepal

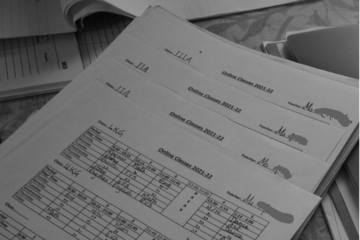

Immediately after receiving this notice, several schools and colleges rushed to conduct exams on 25 April 2021 without adequate safety measures or following the required health protocols. Although the rumours of a potential lockdown were doing rounds throughout the country for several weeks, students were taken aback by the decision of the postponement of exams. Aashish Jha, a first year BSc. candidate at a college in Janakpur, Dhanusha expressed his concerns, “I came to write the exam, despite being totally unprepared for it and keeping aside safety concerns because sadly, COVID isn’t the only issue in our lives. It has been a year of total stagnancy. Once this ends, students like us will be left alone to justify the gap year on our resumes. The truth is, some universities were able to conduct online exams. Not everyone is being left behind. So, I came to at least pass these exams so I feel like I’m going somewhere with my career. Sadly, COVID isn’t the only thing that can kill our future!” Aashish was accompanied by several of his classmates and professors in writing his final exam within 24 hours of notice.

With less than 24 hours of notice, exams were conducted on the last day before the nation-wide closure of educational institutions at a college in Janakpur, Dhanusha | Photo Source: Shivani Mishra

Last year the pandemic caught every sector, institution and individual by surprise. It didn’t feel unnatural to take a sojourn and take in the grief caused by the pandemic. Seeing students all over the world resort to alternate means of learning also acted as a reassurance for students in the developing world of the global severity of this pandemic. Now, schools and universities in several countries are beginning to resume in-person classes as the pandemic is brought to the baseline with mass vaccination drives and strict lockdown measures in the first quarter of this year. Meanwhile, now that schools and colleges in Nepal have been asked to shut only weeks after they fully reopened, students and teachers are beginning to question if yo-yo solutions and temporary fixes will have long term effects on the entirety of the Nepalese education sector and several students will get be left behind in their educational timeline.

Immediately responding to the government order, Private and Boarding Schools’ Organisation Nepal (PABSON) issued a statement urging the government to reconsider their decision of shutting down schools completely. The umbrella organisation argued that closing schools completely in the pretext of the pandemic is not a permanent solution and that continuing in-person classes with adequate safety measures was the only solution to ensure that a majority of students in Nepal can continue their education.

Who gets left behind?

“We’re not all on the same boat, even as we’re facing the same storm”, remarked Aashish, a first year B.Sc. student as he mentioned that he’s afraid of the widening class divide that the pandemic is wedging within the educational sector in Nepal. The very brief 4-sentence notice released by the government asking schools to close in the event of rising COVID-19 cases in the nation, mentions that schools should “resume learning through online classes or alternative methods”. While it is clear that online classes are a solution for the better endowed private schools, “alternative method” reads like an obligatory phrase in the notice to acknowledge a section of the society that cannot access online education.

A private school’s preparations to switch to online learning within a week of reopening | Photo Source: Shivani Mishra

However, in reality, a vast majority of Nepali students in fact do not have access to remote learning . The math is rather straightforward—online classes require a strong Wi-Fi connection if not a 3G broadband access at the very least. While 86% of the state has access to broadband internet , one must also factor the costs involved in attending online classes using mobile data. 1 Megabyte of internet costs a minimum of Re.1, which totals to Rs. 300/hour , even if the classes are attended at the lowest video quality. Other than being an exorbitant amount to spend per hour for several families in Nepal, this analysis doesn’t take into account the households that do not have a spare device for students to use or those that do not have a smart devices/cellphone on which online classes can be taken. Further, internet penetration varies across regions, for instance, a recent survey of access to technology in the western district of Tulsipur showed that only 17% of students had access to wireline internet, of these students, only 6% of the students attended government schools .

Last year, UNICEF Nepal and Sharecast Initiative conducted a nationwide tracking poll, revealing that the most serious impact of the lockdown had been on education. According to the report, of the 95% of students that were out of school, only 52% were studying at home and only 29% had access to formal distance learning, and only half of them were using it. Santwana Mishra, reflecting on her experience as a teacher, expressed that job losses meant that not everyone’s family was able to pay the monthly school fees to access online education even in the capital city. “Several students felt inferior because they didn’t have the latest gadgets or a strong Wi-Fi connection to keep up with their peers”, noted Mishra.

Further, UNESCO estimates show that the pandemic has put 4.5 million girls out of school, and that they are most at risk of never completing their education. According to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics , “crises lead to long-lasting impacts on gender equality and education with irrevocable consequences on the most marginalised girls. The risk of child labour, gender-based violence, early and forced marriage, and early and unintended adolescent pregnancy may increase, leading to many girls never returning to school.”

Hence, it is clear that without proper structures in place, the entirety of the Nepalese education sector is in crisis. The solutions posed by the government only take into account a small number of students who are able to continue learning via online education whilst ignoring a large majority of those who are being left behind.

No end in sight to this crisis

The mental shift of finally preparing to go back to school, adjusting to a new way of being at school with all the safety protocols in place, to going back to online learning within a span of two weeks has undoubtedly had an impact on the overall morale of young students. This week Nepal had over 50% positive testing rates for COVID-19, which has put the entire country in a somber state within a matter of weeks. The mental toll this has taken on young students is largely unaccounted for. Further, the new variant is said to be infecting young children . This will make it even more challenging for schools to reopen in the near future.

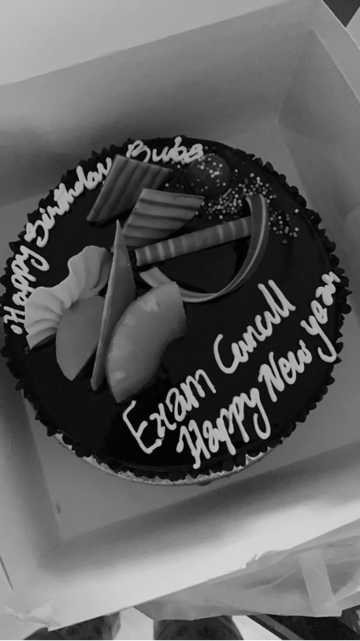

Shutting of schools severs students from more than just academic achievement; students are missing out on crucial and memorable years of school and college life, extracurricular activities, meeting friends etc. Even things like exams which may have seemed dreadful in the past are now being missed. Ekansh Jha, a grade 10 student shared his sentiments upon the cancellation of his grade 10 board exams: “It’s still unclear how our results will be evaluated. My friends and I are a little frustrated because in January, we started preparing for the exams in full swing as though it was really going to be held in-person like any other year. However, things took a turn for the worse very quickly. We started the year with utter uncertainty, and unfortunately we are ending it on the same note. It is mentally taxing.”

Both academically and culturally, the Grade 10 Board Exams are considered an important rite of passage for youngsters in South Asia. “When I first heard the news about the cancellation of exams, I rushed to celebrate. I got a cake for all the pending celebrations that I was holding off through the year because I was busy preparing for the exams. But then as I was cutting the cake, I realized that I couldn’t experience this once-in-a-lifetime catharsis of finishing my first board exam. All the countless hours of preparation, sleepless nights, endless practice papers–for what? Our efforts seemed to have gone to waste. I asked myself, what next? I don’t even know my grades!”

School closures in Nepal are not a new sight. Schools were closed for months at stretch during the 10 year civil war in Nepal, twice in 2015 because of the earthquake and the border blockade. Yet, this time around it’s difficult to see the light at the end of the tunnel. With only 12% of Nepali children continuing their education online and only 5% of the students from poorer families doing so, the Nepalese government, the Ministry of Health and Population as well as the Ministry of Education have a mammoth task ahead of them to contain the pandemic, prevent irreversible negative effects on the country’s educational sector, the overall economy and ensure sustainable and equitable development.

After waiting for nearly 6 months for a decision on the conducting of the grade 10 board exams, a student finally buys a cake on 15 April 2021 to celebrate the cancellation of the exams. He cuts the cake to celebrate everything that was pending because of the pandemic and his preparation for the board exams. | Photo Source: Shivani Mishra

Sources used:

- Dahal, M.S., 2020. Online classes may widen digital divide. Nepali Times. Available at: https://www.nepalitimes.com/latest/online-classes-may-widen-digital-divide/ [Accessed May 5, 2021].

- Paudel, D., 2020. Face-to-face classes online. Available at: https://www.nepalitimes.com/latest/face-to-face-classes-online/ [Accessed May 5, 2021].

- Kunwar, M., 2021. Why girls matter: Working with radios to raise community awareness on girls’ education. UNESCO. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/news/why-girls-matter-working-radios-raise-communi… [Accessed May 5, 2021].

- Samrakshyak, Sharecast. Sharecast Initiative Nepal. Available at: https://www.sharecast.org.np/ [Accessed May 5, 2021].

- Shah, S., 2020. Back-to-School season goes remote. Nepali Times. Available at: https://www.nepalitimes.com/opinion/back-to-school-season-goes-remote/ [Accessed May 5, 2021].

- Times, N., 2020. COVID-19 impact on food and school in Nepali children. Nepali Times. Available at: https://www.nepalitimes.com/latest/covid-19-impact-on-food-and-school-in… [Accessed May 5, 2021].

- UNICEF 2021. Don’t let children be the hidden victims of COVID-19 pandemic. UNICEF. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/nepal/press-releases/dont-let-children-be-hidden-… [Accessed May 5, 2021].

Author Information

Shivani Mishra is pursuing an MSc. in Modern South Asian Studies at the Department of Global and Area Studies at the University of Oxford. Her research interests lie at the nexus of women, peace, and security in South Asia with a focus on post-war female political participation in Nepal.

Suggested Citation

Shivani Mishra. 2021. ‘Education in Crisis: Nepal’s educational sector in the pandemic’, Think Pieces Series No. 14. Education.SouthAsia (https://educationsouthasia.web.ox.ac.uk/).